Thoughts on React Native

I’ve been a native (emphasis mine) mobile developer for many years, having learned on iOS 31; and ever since, I’ve been a staunch supporter and firm believer in native-only development. Cross-platform development? Eww, gross, and language please; those words are dirty. No thank you, sir. I’m a clean developer, a master craftsman who actually cares about their work. I don’t slop things together in whatever language. No, I use objective-c Swift. Native-first, native-only, hoo-rah (fist pump)! I breath rarified air from a bag.

Until I don’t.

Cause, you know, clients: they screw things up. I want beautiful code, SRP, unit tests, architecture… my code must sing in perfect tune. Clients just want the damn thing to work (as if that really matters2) and they want it at the cheapest price possible. So, of course, some grungy kid comes along with their java-whatever and whispers dirty somethings in the client’s ear. Oh and you know what they’re saying. You know what lies are slithering down that client’s ear canal. You’ve heard them before. It’s the same thing every year, every decade: the promised land, just out of reach, almost there but never actually. It’s:

One codebase to rule them all. Write once, run everywhere, cross-platform bliss in a bottle.

The heavens open up, realization dawns, and the client suddenly understands: all their dreams can come true, and all within budget.

And every developer over the age of [redacted] just fell off their chair from a very hard eye-roll. They’ve heard this siren before and walked right off the ship’s bow. Maybe they’ve even kissed it, done things with it they would rather forget, and realized the inevitable truth: cross-platform doesn’t work. It never did, never will, and might as well be hell dressed up in a toga with wings. Oh, it looks good on the outside, but dive down and— oh my god what is that?

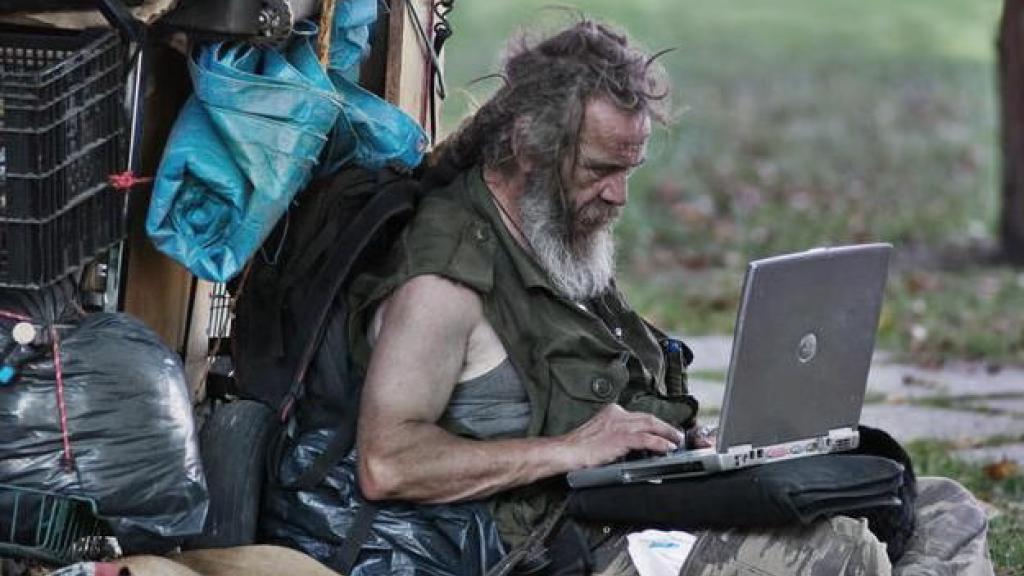

The problem is simple: clients. They demand things because, you know, they’re the ones actually paying for shit and without them we could encode heaven’s very beauty into carefully colored text; but then we wouldn’t eat, we’d loose our homes, our spouses would leave us, our children would starve, and suddenly:

But my code is perfect!

So when the client comes to you and starts talking about PhoneGap Ionic Monica Cordova Xamarin Mandalorian (No wait, that one’s actually good!) NativeScript … oh, there it is: React Native. Right, so when they start speaking of that, you do what any respectable developer does: You tell them of course you know it (who doesn’t?), while frantically cloning the tutorial repo onto your computer. Or maybe, if you’ve got an honest streak, you admit you don’t know but then quickly follow with a confident assertion that you’ll master it by Friday.3

Congratulations, you’re now a React Native developer. And this is how angels fall.

Now that you’ve descended from on high into the muck of this existence, let’s talk about some hard lessons. React Native is Javascript, Javascript is of the devil, and yes, while you may have fallen, that doesn’t mean you should continue your descent right into that particular hell. Our muddied existence is a nice compromise; so whatever you do, don’t use Javascript.

For years now, Typescript has been slowly shoving Javascript out to become the de-facto language of the web. I think we’re at the point where it’s more common than not, even to the point where it’s actually kind of easy to add it to React Native. 4 It is itself a superscript of Javascript, meaning it compiles down into Javascript, and it’s vastly superior in pretty much every way, retaining the best features of its dirty origins, while adding features desperately needed by real developers making real applications: actual types.5

This is not a how-to piece, so moving on…

My experience with React Native has been a surprising… well, it works. It’s not hell, nor heaven, but somewhere in the mud. There’ve been times I’ve cursed its very existence, spending days tracking down some weird issue, but then most of my time has been fairly mundane. It’s fine. React Native has its own paradigm, one you should learn and know, but that’s true of every language and platform.

I’ve found it interesting that both iOS and Android appear to be moving closer to the React Native paradigm rather than the other way around. The first time I saw SwiftUI, I was struck by how similar it was to React Native’s state-based UI system: you describe the UI, then update the state. The “system” then updates the UI based on the state. This, in addition to the intended unidirectional flow of data, makes the two systems rather comparable even if the syntax and language are different.

After several years of both React Native and native-only development, I’ve been forced to admit that React Native has a place in mobile development.

Please put down the knife. Just hear me out… and maybe wipe the spittle off your face.

When native developers defend their domain, it’s usually along the lines of: cross-platform can’t possibly get the performance, design, customization, attention to detail, and general craftsmanship of native code. You know what, they’re generally right. Not only can you not get the same level of all those things, but the act of writing one codebase for two very different platforms requires a certain level of compromise. Either Android will look like iOS, iOS will look like Android, or the app will sit some where in the middle. It’s just the nature of the beast.

Not only that, but React Native is running Javascript on top of the native framework, and Javascript is always going to be slower no matter how it’s compiled and run. Some of this is mitigated by using native components, but no matter how you spin it, you still sacrifice performance.

The other argument I hear from native developers: By the time you work around React Native’s issues, you might as well have written two separate, native codebases. And you know what, they’re right. They’re also wrong. Life is more complicated than platitudes, and the truth is more subtle than blanket statements. Yes, there are times when this is true. Yes, there are times when this is wrong.

It’s important to know when those times are.

Because here’s the dirty truth: a lot of apps don’t need to be carefully crafted. They need to be usable and sufficient, but not works of art; they need to be developed on a budget; they need to be developed by a single developer; they need to be developed quickly; they don’t need a ton of custom, low-level code… you know what, I could go on but I think you get the point:

For a lot of apps out there, React Native is enough, and it’s cheaper than developing two separate codebases… just like the charlatan said.

Sacrilege! But you know it’s true, and I kindly ask that you remove the knife from my throat. It won’t change anything. So many of us native developers have idolized the craftsman’s approach and forgotten that many clients just want a usable app and don’t care how much attention to detail you’ve put into the project as long as it works reasonably well for a good price.

Now let me take a step back and explain what I’m not saying.

I’m not saying you should throw you hands up, grab the whiskey bottle by the throat, and settle for an oblivion of alcohol-induced shitty code. I’m not saying you should sacrifice good software development practices, or forego SRP, or give up Unit Tests, or give up good software architecture.

You can write good code in React Native.

It’s true.

Just because a lot of people don’t, doesn’t mean you can’t. This is why I practically demand you use Typescript. Once you’ve become accustomed to React Native’s paradigm and structure, there’s nothing to prevent you from architecting good, well designed, sustainable code… unless you’re using Javascript, in which case I recommend you take another swig from that bottle and resign yourself to numbed mediocrity. Yes, there will be compromises,6 but those compromises aren’t in the code itself; they’re based on targeting two different platforms with that code. The code can be good; the code can even be great, something to be proud of, and the app will work well.

It’s fine, and that’s the point. React Native is just one more tool in the belt. There are times when you want to use it, and times when you really shouldn’t. There are apps I’ve written in native that I couldn’t fathom trying in React Native, apps I’d refuse to write in React Native. There are apps I’ve written in React Native that I can truly say would be a waste of time to write in native and completely unnecessary.

It’s a tool, nothing more. We need to stop treating it like a crusade and realize it’s here to stay.

There’s a logical fallacy that parents like to throw at each other. It goes like this: well, my kid never does fill_in_the_blank. The response is simple: until they do.

Your daughter is an excellent climber and will never fall out of the tree, until she does.

Your son would never play with a snake, until he does.

Cross-platform development will never be a feasible solution, until it is.

This is what all the hard-eye-rolling, [redacted]-age developers have missed. Just because it hasn’t worked in the past, doesn’t mean it won’t in the future. The truth is insidious: cross-platform development may not have worked well, but it’s been slowly getting better for years. And now, it’s good enough.

Does this mean native development is out? Should native developers flee their platforms and flock to the nearest compromise? Naw. There are lots of scenarios that will never work in cross-platform development. There’ll always be space for craftsmanship. Native development isn’t going anywhere. But then, neither is cross-platform.

It’s time to we accept the truth: cross-platform development serves a roll that won’t be going away. React Native might someday go away, but if it does, it’s because a better development platform has come along. For now, it’s one of the best out there and it works better than you might think.

Welcome to the death-march of progress. Now go grab a cup of coffee, maybe pour some whiskey in it, clone that tutorial repo, and get learning. React Native developers are in demand and pay well. I can tell you that having experience in both native and cross-platform development bodes really well for your job prospects.

Or don’t.

Nobody’s forcing you to learn React Native. 7 Mobile development is a massive industry now so there’s plenty of space for both. Just realize that React Native isn’t dirty, and no matter what the acolytes or evangelists might claim, it’s never going to replace native development. It’s just another tool and the sooner we accept it, the sooner we can get back to the business of making great apps.

-

Or maybe 4? I know I released my first app on iOS 4, but I can’t recall if I actually started in iOS 3. Let’s just say 3, cause it sounds better, right? Also, that fish I didn’t catch because I don’t fish was at least 80 lbs. ↩

-

I mean, come on! I’ve got hundreds of unit tests and they all pass. What the hell are you complaining about now? ↩

-

Just be careful not to mention which Friday. ↩

-

Adding Typescript to RN used to be a multi-hour process, and that was when you knew what you were doing. My first attempt took me two days, and required combining the advice from several different blogs/tutorials to get it to work. And it was still worth it. Now days, it’s a simple babel extension (which is installed by default) and a tsconfig file. You have no excuse. Use Typescript. ↩

-

Sort of. It still compiles to Javascript, so many runtime features you might expect aren’t there. Typescript is all about compile time safety, but once compiled, the wild west of Javascript takes over. You’ll feel this whenever you try to check if the object you have is the type you expected only to find you can’t, though there are hacks around this. ↩

-

But let’s be honest: when is that not true, even in native development? There are always compromises. Figuring out the nature of the compromises and aligning them with the project is a big part of software development. That will never change. ↩

-

Setting aside client demands, of course. ↩